A year ago, we were just getting comfortable with prompt engineering. Vibe coding wasn’t yet common parlance. A lot changes in a year. Today, Copilot is an ever-present companion for many of us, and getting the most out of it is an ever-evolving part of the practice of development.

Just as effective prompt engineering makes a big difference in the quality of output you can get from an LLM, the right guidance for Copilot will help it produce better work - especially in agent mode. This article will focus on creation and use of Copilot-instructions to guide operation on a repo-by-repo basis, but before diving in, let’s review a few options in this ever-evolving area.

Instructing Copilot

The principle difference between prompt engineering and Copilot instructions is that prompt engineering tends to be transient and is certainly localized to your account-specific context.

It’s true that Copilot Memory is attempting to fill this gap, and given emerging tools like OpenClaw, the transient nature of prompt engineering seems sure to disappear, but instructions that stick to you individually won’t maintain consistency in a team setting.

Enter Copilot-instructions, which let you save your project-wide Copilot instructions in a file that lives with your repo, visible to anyone who pulls your repo. We’ll explore this option in depth shortly, but keep in mind this is not the only option to capture design and coding guidance for AI coding tools.

For guidance that can extend across multiple repositories, consider MCP integration with your project organization tool of choice. Atlassian offers an MCP server for its cloud-hosted Jira and Confluence, and Microsoft has a similar MCP server for AZDO, as well as a Copilot connector. Of these tools, the only one I’ve tried personally is the Atlassian MCP server, which operates mostly as-advertised. Note that when used properly, the MCP integrations above can guide programming standards across all your code bases all at once, which is the stuff of dreams for enterprise architects - as long as these standards can be expressed efficiently and effectively. It’s also worth pointing out that all these techniques can coexist, with Copilot-instructions operating in a bootstrapping manner to access enterprise-wide standards.

Getting Started

The basics for Copilot-instructions are as simple as could be - simply drop a file called Copilot-instructions.md in a .github folder in your repo. Docs from github will go into detail on options like instructions that apply only to some paths or some agent LLMs. This page also offers a prompt you can use to generate a Copilot-instructions file based on your existing repo, and that’s what we’ll try here.

For this example, I’m using a simple solution I created to explore vertical-slice architecture in dotnet Aspire. You can find the “before” version of this repo here: https://github.com/dlambert-personal/AspireTodo

For this demo, I’m going to use the prompt shown in the github docs verbatim. I do believe that were I doing this in earnest, I’d want to customize the prompt somewhat. I may also want to explore how this prompt works against repos of varying size, maturity, and cohesiveness. For instance, the bit where we ask Copilot to derive architectural elements of the project is especially interesting. In a trivial example like this, I expect Copilot to find those elements quite effectively, but in a larger repo – one with some development history – I wouldn’t be surprised to see the model struggle a bit. For reference, I’m using the Claude-Haiku 4.5 model in agent mode.

Reviewing the Results

So, how did the prompt do in its out-of-the box form? Really not too bad; there’s some great content here. My chief criticism (and one that’s easily corrected) is that I believe much of the generated content would do well migrated to the readme.md file, which I’ll do when I commit the “after” results to a new repo. So, section-by-section, here’s what was produced.

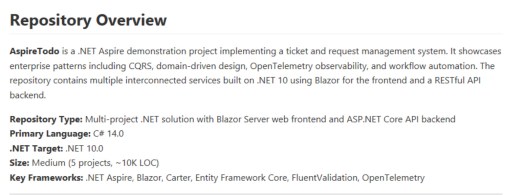

- Repository Overview. A good summation of the solution - probably better-suited to live in the readme. All the information cited here is accurate and useful.

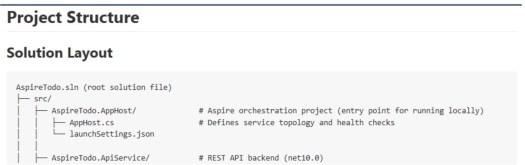

- Project Structure. Definitely useful, and definitely a section I’d look to move to readme. In fact, I believe I’d replace this in the instructions file with an explicit instruction to keep this area current as the project evolves. Along these lines, I’d like to see how Copilot handles the project as it grows in size. The level of detail shown in this section could grow unwieldy in a larger solution.

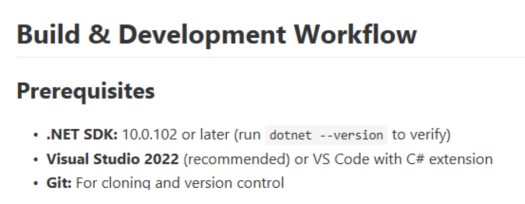

- Build & Development Workflow. I found this section interesting. It’s the first place I spotted an outright mistake (indicating that VS2022 would be able to work with .Net 10). Beyond that, the instructions seem thorough and useful, including some startup alternatives that could prove helpful and database setup and migration instructions as well. Once again, it’s possible much of this would be well-suited to live in the readme file.

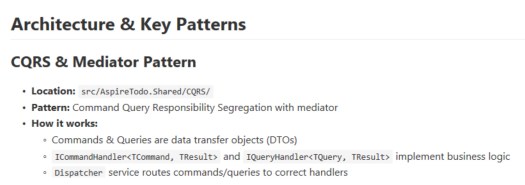

- Architecture and Key Patterns. An excellent section that summarizes design patterns and key integrations. Again, frankly, one could argue this material could live in the readme.

- Common Tasks & Gotchas. This section began to get a bit odd. There’s a bit on adding a new API endpoint that’s pretty good, but there’s also a bit on debugging JSON deserialization that seems like pretty general debugging techniques I’d expect to uncover when needed in Ask mode.

- Known Issues & Workarounds. This entire section suffers from the same problem - this entire section should be discoverable when needed and debugging topics shouldn’t be limited to the few topics presented in this section.

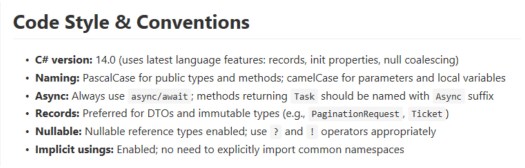

- Code Style & Conventions. A short, but useful section - definitely one I’d keep in instructions and expand upon. In my opinion, this is exactly the sort of guidance I’d want to see in Copilot-instructions. Expanding on this area could help keep coding style consistent as the codebase evolves - one of the main objectives of Copilot-instructions in the first place. If you begin orchestrating instructions across repos (using MCP connections to a wiki, for instance), conventions like this would be appropriate for enterprise-wide use.

- Troubleshooting Build Failures. Back to material that should be general knowledge.

- Final Notes. Another useful section I’d keep and expand upon. The are specific instructions to the Copilot agent - again, exactly the instructions I’d want to see in this file.

Putting it to the test

Before I fine-tune the instructions, I wanted to test Copilot to see if it seemed any smarter with the addition of the initial draft. I made a copy of the original repo (so you can see the “before” version) and asked Copilot (still using Claude 4.5) the following:

This solution needs to be refactored to account for a name change. Replace all references to AspireTodo with AspireTickets. Include solution name, project names, namespaces, component files, and variable names. As always, the solution should build successfully when you're done.

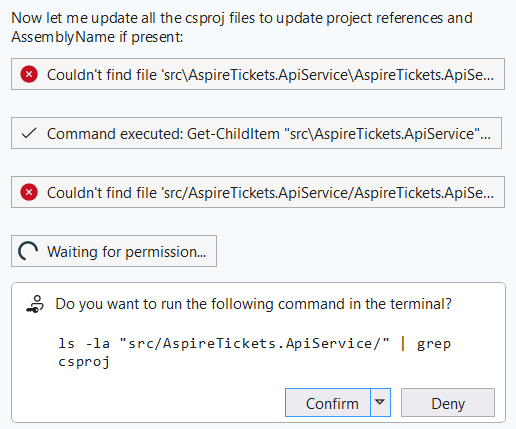

Copilot plotted a six-step plan and got stuck on step 2:

This refactoring is extensive. Let me take a systematic approach:

1. First, I'll gather all the source files that need namespace updates

2. Rename directories and projects

3. Update all namespace declarations

4. Update project references

5. Verify the build succeeds

This is a problem I’ve seen frequently with Copilot: the powershell integration has a tendency to fail or freeze. After closing the terminal, Copilot realized it needed another approach, and it tried again. This went on for a while - the whole time showing success sprinkled with failure. Had this been an actual developer, I’d have stopped them and suggested they revisit their plan, as it sure looks like a lot of guessing going on here. The “stuck in powershell” problem continued as well – it seemed like Copilot expected powershell to understand commands that powershell just whiffed on - despite my installation being reasonably current.

Finally, adding insult to injury, Copilot eventually just stopped working new tasks - apparently before it was done. I gave it a little nudge, and sure enough - there was a little more work to do.

Finally - the build. First attempt: five errors and two warnings. All five errors were project files not found. Copilot blamed them on Visual Studio’s cache, which seemed like a class-one cop-out.

More confusion… more freezes. Eventually, Copilot froze hard enough I couldn’t even cancel in the chat window, so I took matters into my own hands. It turns out that aside from the file renaming issues, Copilot had gotten pretty close. I had one “using” statement I needed to patch, and all the project files had to be removed and re-added, but once that was complete, I was back to building w/o errors again.

When all is said and done, did Copilot save me time in this refactor? Maybe - but not by a ton. I think the level of supervision is still quite high, but the remaining rough bits seem like they’re not so much a model shortcoming as an integration snafu - hopefully an easy update.

Next Challenge - adding to the UI

I suspected Copilot might do better with a change that didn’t require so many file manipulations, so I gave it a simple prompt that would require touching the solution in several places:

Modify the current page to be able add tickets in addition to displaying them. Use the CreateTicket command in the API project to save the new ticket.

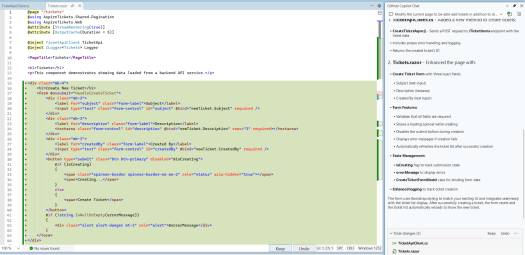

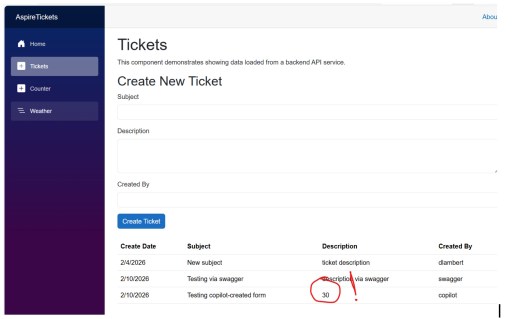

This request was dispatched quickly, and seems to have produced a high-quality output:

The project still built, and when I ran it, I saw a plausible-looking form. The bad news: the form wasn’t submitting anything to the API, so I asked Copilot to fix it. The resulting back & forth was almost comedic. I wasn’t about to let Copilot off the hook, and it did eventually figure it out. I’d begun counting form submission attempts, and (if my count was right), it took well over two dozen stabs at this to get the form to submit successfully:

It could be argued that very little architectural guidance was provided to Copilot in the instructions we’d created, so the Blazor form submission stuff it struggled with might almost have been excusable. I’m still a little disappointed here, though, because the real gotcha seems to have been an addition to .NET 10 (@rendermode) that was keeping the form from operating interactively, and the .NET version absolutely was covered in copilot-instructions.

For the last test / evaluation, I’m going to switch from Visual Studio 2026 to VS Code, and I’ll modify my prompt to specifically call out use of copilot-instructions, though I don’t believe this should be necessary. This is the prompt used (including a typo on “architectural”):

Modify the solution to be able edit tickets that have been previously saved. Use copilot-instructions.md as a reference to architecural norms in this solution. Include UI changes to the Tickets page to load a ticket to the form for editing and submit changes to the API. The API project will need a new EditTicket command to save the ticket.

I’ll be honest - I wasn’t expecting a drastic change in experience going from Visual Studio to VS Code, but wow, what a difference there was! The initial change was quick, and as near as I can tell, perfectly functional. I got an updated form that works as expected, the API adapter works, the API has been extended to include a new command, and the new command follows the design conventions in use by previous commands. VS Code even asked me if I wanted it to test the new functionality, and that went slightly less-well – the spots where Copilot integrates to the world around it really do seem to be its Achilles heel right now.

Up to this last step, I believe I’d have given Copilot a barely-passing grade. A co-worker from years back always used to remind me we don’t cheer for the dancing bear because it dances well – we cheer because bears aren’t supposed to dance at all, and this is about how I’d have summed up my experience with Copilot in Visual Studio. Copilot in VS Code, on the other hand, seems much more well-sorted.

I’m still impressed with the amount of project documentation Copilot was able to sift out of my project, and I intend to press on with pulling some of the docs into readme and fine-tuning the bits that are left to be more prescriptive – in short, leaning on this a little more to get a feel for the edge cases.