Commonly, when people think "user experience", they think about screen designs. Apps, web pages, Figma -- all that stuff. The shift from UI design to UX alone is a nod to this practice being more than skin-deep, but I still think a lot of the deeper behavioral aspects of user satisfaction are lost on many -- especially people who have only a casual interest in UI/UX.

I believe there are clues all around us, though, that we can take advantage of if we pay attention. I'll begin with the premise / reminder that real usability is completely invisible. You can only see usability by the absence of impediments to usability. In short, a system is usable when it does exactly what a user expects, even if they can't articulate those expectations.

One of the best examples of invisible usability can be found in Visual Studio, which has been a market-leading IDE for decades now. Built by developers for developers, they've gotten a lot of things right, and even though you're probably not building a tool for use by developers, some of these lessons likely can apply for you, too.

Starting Fresh

Right off the bat, Visual Studio shows its usability by setting users up to be successful when working with a new project. Pick any template you like in Visual Studio, create a new project from it, and it will build successfully. While it might not seem like a big deal, it makes a lot of difference for a new user learning one of these technologies. The ability to start from a solid foundation gives that user confidence to build on that new solution.

What's the lesson? Be aware of the "getting started" experience for your users. Anything you can do to start a user more quickly and with more confidence will help them start using your software with confidence. When users get started with confidence and gain momentum, they're more likely to persevere a bit more if they get stuck later, too.

Save Always

Another subtle way Visual Studio helps is one you probably never gave a second thought. No matter what state your working files are in, you'll never mess one up so badly that Visual Studio won't let you save your work:

A more elegant take on this is to save automatically, so if something goes really wrong, you have a recovered version of your work (which Visual Studio obviously does). Note that automatically saving can actually introduce some small usability hiccups of its own, but that's a problem for another day.

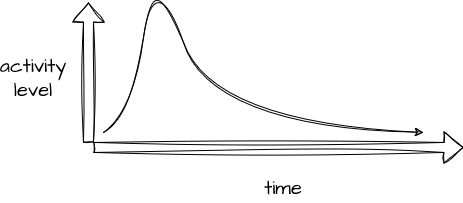

What's the lesson? Document-based applications like Visual Studio and office apps (spreadsheets, docs and the like) typically consider this sort of behavior table stakes these days, and it's not likely you're building one of these, but watch out for behaviors that cause a user to not be able to save work-in-progress. In a UI, you may run into this if you've got a bunch of required fields on a page, and as the field count goes up (and maybe the page count, too), expect that your users' frustration level will go up, too.

It's actually a lot more likely that you'll run into this problem in your APIs. For example, here's a simple method I used in a post about fluent validation:

public ActionResult CreateDealer(Dealer dealer)

{

Guard.Against.AgainstExpression<int>(id => id <= 0, dealer.Id, "Do not supply ID for new entity.");

var dvalidator = new DealerValidator();

var result = dvalidator.Validate(dealer);

if (result.IsValid)

{

_sampleData.Add(dealer); // SaveChangesAsync() when working with an actual data store

return CreatedAtAction(nameof(CreateDealer), new { id = dealer.Id }, dealer);

}

else

{

return BadRequest(result);

}

}

While this method effectively validates inputs, the return results to the user aren't especially helpful, and as an object like this scales up in size, it's more likely that a consumer will have partial inputs that don't pass all validation criteria. Rather than preventing this from saving altogether, consider structuring an object like this so that as many values as possible are optional for saving -- even if they're needed in order to have a "valid" object.

In this simple example, we can create a result type that appends a ValidationResult property to the model. We'll return this instead of the "naked" object to show the validation propertied next to the model. The result object is preferrable to embedding a ValidationResult in the model because this keeps the request intact -- there's no reason for the ValidationResult to be part of the CRUD requests.

public class ModelValidationResult<M, V> where V : AbstractValidator<M>, new()

{

public ModelValidationResult(M model)

{

this.Model = model;

}

public M Model { get; private set; }

public FluentValidation.Results.ValidationResult ValidationResult { get; set; }

public bool Validate()

{

V validator = new V();

this.ValidationResult = validator.Validate(this.Model);

return ValidationResult.IsValid;

}

}

With Validate in the Dealer object, the controller method also becomes a bit simpler:

public ActionResult CreateDealer(Dealer dealer)

{

Guard.Against.AgainstExpression<int>(id => id <= 0, dealer.Id, "Do not supply ID for new entity.");

ModelValidationResult<Dealer, DealerValidator> res = new ModelValidationResult<Dealer, DealerValidator>(dealer);

res.Validate();

_sampleData.Add(dealer); // SaveChangesAsync() when working with an actual data store

return CreatedAtAction(nameof(CreateDealer), new { id = dealer.Id }, res);

}

Note that I left the guard clause in place here -- there will still be some validations that really need to prevent saving bad data, but now that these changes are in place, it's possible to save an object with incomplete data.

This technique won't work in all cases, but consider it if you can support saving objects with a minimal set of data and check for a fully-populated object later.

And more!

If you view Visual Studio with an eye to borrowing UX techniques, you'll see more lessons like these - the Dynamic Validation example I covered earlier is an example. Since you're probably not building an IDE or even a tool for developers, you'll need to interpret some of the techniques liberally, but I assure you the lessons are there. You may also see some negative usability examples -- in fact, sometimes these are easier to see because they get in our way and draw our attention.

If you're interested in source code for this examle, you can find it on Github: https://github.com/dlambert-personal/CarDealer/tree/Guard-vs-validate