I'll just grab a cup of coffee, ok?

Almost a great idea

Here's an example of a good idea gone wrong. I saw a link for a web site that exists solely to advance openness in government. How cool is that?

I clicked around for a bit, eventually reaching a place where I was supposed to be able to submit an idea for government, where it would (presumably) be viewed and discussed among my peers. When I clicked the button to enter my idea, I was prompted to log in with OpenID (again, very cool). I logged in and clicked the button again, and was rewarded with the following barfage:

500 Servlet Exception

[show] java.lang.NullPointerException java.lang.NullPointerException at _jsp._jsp._includes._build_0header__jsp._jspService(jsp/includes/build_header.jsp:37) at com.caucho.jsp.JavaPage.service(JavaPage.java:61) at com.caucho.jsp.Page.pageservice(Page.java:578) at com.caucho.server.dispatch.PageFilterChain.doFilter(PageFilterChain.java:195) at com.caucho.server.webapp.DispatchFilterChain.doFilter(DispatchFilterChain.java:97) at com.caucho.server.dispatch.ServletInvocation.service(ServletInvocation.java:266) at com.caucho.server.webapp.RequestDispatcherImpl.include(RequestDispatcherImpl.java:494) at com.caucho.server.webapp.RequestDispatcherImpl.include(RequestDispatcherImpl.java:358) at com.caucho.jsp.PageContextImpl.include(PageContextImpl.java:1008) at _jsp._jsp._includes._autoselect_0header__jsp._jspService(jsp/includes/autoselect_header.jsp:23) at com.caucho.jsp.JavaPage.service(JavaPage.java:61)....

Close, guys. Very close!

Please don't do this to your customers, okay?

More on “HTML is dead”

Microsoft's S. Somasegar ("Soma"), who heads the Developer Division, posted on his blog yesterday about "Key Software Development Trends".

I was pleased to see him include "Proliferation of Devices" among the top trends in development, but there was obviously an acute case of tunnel vision at work here, because Soma completely neglected all the non-Microsoft devices that people seem to insist on using. I know, I know -- you can't have a Microsoft VP publicly acknowledge Apple on a corporate blog; that's just craziness, but the rest of us sure can.

- Image by . SantiMB . via Flickr

As I wrote in my last post, the proliferation of devices -- especially across platforms -- has the potential to impact me in a pretty fundamental way. It wasn't long ago that I could develop a web application and have a reasonable expectation that most clients could use it, regardless of their client architecture. Differences existed among browsers, to be sure, but there were relatively few "can't get there from here" moments.

- The desktop. Obviously, this is where Microsoft lives. Between Windows and Office, this is not only where Microsoft asserts its most solid dominance, it's also where they make most of their money. In terms of technology adoption, though, they're facing a 1-2 punch: they've struggled to get people to upgrade Windows, and they've struggled to get people to upgrade IE6. The Windows upgrade problem also impacts SilverLight availability, since most people get SilverLight with an operating system upgrade. According to Riastats.com, SilverLight's current penetration is just above 50%, which is a good start, but not yet where it needs to be. Adding insult to injury, more people are running Mac OS every day, and Linux continues to grab scraps of market share, too.

- Internet Explorer. When people leave IE6, there's a good chance they're going to FireFox or Chrome instead of to IE8. Microsoft's once near-monopoly in browsers has been eroding over time. It's now imperative that any UI technology that runs on a browser must run on most, if not all of them.

- Windows Mobile. The delay in getting Windows Mobile 7 out the door has absolutely killed Microsoft here. They got caught by the iPhone in much the same way they were caught by the internet, and we've yet to see a credible response. At this point, even Mobile 7 is lights-out fantastic, it's got a pretty huge uphill battle to gain relevance, let alone dominance.

- XBox. The XBox is a real success story at Microsoft, but again, it's not dominant, with a market share somewhere around 25% of all gaming consoles.

There's no question that what Microsoft really wants is for us to develop software with Microsoft tools on a PC running Windows, and then to distribute this software to consumers who are also running on a Microsoft-powered device of some sort. When Microsoft held near-monopoly positions on every platform where computing reasonably occurred, this was tenable. Today, though, it's just not reasonable. Customers are computing on a dizzying array of devices, and not all of them are powered by Microsoft.

What's needed today from Microsoft is real development leadership. Give us a runtime that works everywhere, and Visual Studio becomes an absolute no-brainer choice for development. While this might seem like a daunting task, a good part of this work is already being done. Miguel de Icaza's efforts with Mono have paid incredible dividends to-date. Today, because of Mono, you can:

- Run C# code on Linux.

- Develop C# in an IDE on Windows, Linux and Mac.

- Write .Net code that deploys to J2EE application servers as Java bytecode.

- Run SilverLight on Linux-based machines.

- Write C# applications that run on the iPhone.

- Write games for Windows, Mac, and iPhone.

- Write C# applications that run on Android phones (okay - this one isn't ready yet, but it's coming!)

Microsoft, please jump on this bandwagon! Visual Studio is so clearly superior to other development environments that its only current threat is developers hemorrhaging to develop for other platforms. Making Visual Studio a true cross-platform tool could make that argument a non-starter.

Similarly, SilverLight could very easily overtake Flash as the most widely-available rich UI runtime, but support for more mobile platforms will surely help this cause. In a recent blog post, Miguel talks about a library for the iPhone that helps define UI's more declaratively -- a trait SilverLight already handles well.

To envision the kind of difference this could make, imagine launching Windows Mobile 7 with a few thousand iPhone apps ready to run on it. This makes WinMo7 a much easier switch for consumers, and it could be a reality if we were already developing iPhone apps in C#. Aren't the folks in Redmond sick of seeing every company from Dominos to Nationwide Insurance telling us to download their iPhone app? Why not level the playing field and let these companies publish an app that works on any phone?

It's within reach.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Windows Mobile Down Sharply, Linux/Android Up Sharply (boycottnovell.com)

- Microsoft's Gadgets/Hardware Business is Collapsing (Zune, Xbox, Mobile) (boycottnovell.com)

- How Microsoft's New Mobile Approach Stacks Up with Apple and Google (xconomy.com)

If HTML is dead, what’s next?

The introduction of Apple's iPad got a lot of people talking about "apps" again. There's no denying the oppressive popularity of apps today; everybody's got an app store and everybody's playing catch-up with Apple. Apps are the new hotness.

Yesterday, Stephen Forte (Is the iPhone (and Android) the harbinger of death for web pages?) observed that apps kick the crap out of web pages when you're on a mobile device, which is why we're seeing an app revolution similar to the one that launched HTML (and the web) to prominence a decade ago.

- Image via Wikipedia

The part he missed, though, is the negative impact of a fractured client landscape.

When you see a Fortune-500 company announce a new iPhone app, do you ever wonder what it expects its Blackberry customers to use? How about Android? Is the cost of the new app hotness a need to build four copies of every app?

On iPad day, I caught an interview on NPR's "Marketplace". Josh Bernoff from forrester.com was talking about how the web is effectively shattering due to the different experiences on each of these platforms. To me, this demonstrates that we're in the midst of a fundamental transformation.

The web (specifically, HTML) was the great equalizer. Any server could serve any client. This simple concept "made" the web. We're now experiencing a shakeup to this universal access. The web is now accessible to more devices than ever, but the cutting edge is rich client development (apps), and this is hugely fractured. On the web, we have technologies like Flash and SilverLight, and on mobile devices, you can develop for iPhone, iPad, Android, BlackBerry, Palm Pre, Windows Mobile, and others.

Today's development tools give us no practical way to target all (or even most) of these client platforms "natively". This is not due to technical impossibility; it's a function of the power struggle that's occurring among these warring platforms. If Microsoft and Apple both wanted to see SilverLight run on an iPhone, I'm confident that it would have happened by now.

Instead, all the major players in mobile platforms want to own that whole space, and their proprietary UI's are required for this. If Apple, Windows Mobile, and Android all ran flash, for example, Apple's dominance in mobile devices would be severely compromised (after all, I can get the same "apps" on any device at that point, right?). Apple doesn't want to see this, obviously -- it takes money directly out of their pockets.

The impact of the splintered web on developers is twofold. First, and most obviously, every app must be coded from scratch to run on each platform a developer wishes to reach natively. This is going to force a pretty uncomfortable reckoning with Product Managers, and it's probably going to mean that in many cases, only the top one or two mobile platforms is served, leaving the rest of your customers to eat HTML table scraps.

The second impact on developers is a splintering of skill sets and tools. If I want to port my .Net application to iPhone / iPad, I'm looking at a sizable intellectual and financial investment. At a minimum, I need to buy an Apple computer, because you can't do Apple development on a Windows box (no monopoly there, right?). Only then can I even begin to try to port or rewrite the app. Tools like MonoTouch can help preserve my business libraries, but the UI transition won't be seamless.

In practical terms, the specialization needed to be good at developing for any of these platforms also means that any one developer can't be great at all of them, which implies that I need multiple developers to target multiple platforms. This is starting to get expensive, now, isn't it?

In time, it's inevitable that the market will work this out. One of the major platforms will win, relegating the others to the "Island of Misfit Technologies", or a number of them will agree to interoperate (via Flash, SilverLight, HTML 5, etc.). In the mean time, though, businesses need to expect more expensive development if they want to reach all their users with native apps, and developers had better be prepared for more UI platform changes.

Do you miss the good old days of HTML already?

Related articles by Zemanta

- A Web Without Flash? (mikebrittain.com)

- Developer Sourcebits puts focus on iPad apps (macworld.com)

- Why we should pay more for our phone apps | Victor Keegan (guardian.co.uk)

Do you need a smart customer?

I consider myself something of an amateur photographer (yes, in case you're wondering, the photos are mine, be they ever so humble). By amateur, I mean in part that I've learned enough to know where I stand against the ranks of really good photographers. Among other things, I've come to understand that there's a lot to learn about photography before you can really hope to be good, but I also understand how people come to believe that they can be pro photographers just going out and snapping up the latest and greatest hardware.

The advent of digital cameras made photography accessible to a lot more people by making photography cheaper and easier by a pretty huge increment relative to film photography. Once you've bought a camera, it now costs next to nothing to go out and shoot a couple hundred pictures in a day. Since you can see your results immediately, you can also make changes to settings or composition in real time, which massively increases a new photographer's learning curve. Bottom line: you can go from zero to decent in a very short time.

"And what," you might be asking, "does this have to do with software?"

One of the problems facing both photographers and software professionals, it turns out, is that it's pretty difficult for an uneducated consumer to tell the difference between "passable" and "really good". This morning, I read a really interesting article by Scott Bourne: And You Call Yourself a Professional? In this article, Scott bemoans the fact that there are budget photography "pro's" who are dramatically undercutting really good photographers, producing mediocre results for the client and, in Scott's words, these proto-pro's are "dragging down an entire industry."

One of the problems facing both photographers and software professionals, it turns out, is that it's pretty difficult for an uneducated consumer to tell the difference between "passable" and "really good". This morning, I read a really interesting article by Scott Bourne: And You Call Yourself a Professional? In this article, Scott bemoans the fact that there are budget photography "pro's" who are dramatically undercutting really good photographers, producing mediocre results for the client and, in Scott's words, these proto-pro's are "dragging down an entire industry."

My first reaction, of course, was that this is one of the fundamental problems in our industry, too. Good developers can spot bad developers a mile away, but customers and employers can't do this -- at least, not until they've become somewhat educated in the intricacies of software development. This is one of the key ideas in another one of my recent posts: Fixed bid isn’t nirvanna.

Is it really reasonable to expect that bad photographers or software developers are going to take themselves out of the market? Not really. In a well-functioning market, they're either going to improve or be driven out of the market, but they're certainly not going to experience a crisis of conscience and change their ways if customers are buying this stuff.

Instead, Scott's “We fix $500 wedding photography” idea is probably a lot more effective. Customers need to understand how they're affected when they bite on low-ball services, but this is no small feat. Think about it: if a customer is shopping for a deal, you're going to have a hard time explaining to them exactly what can go wrong by taking short cuts.

In photography, there's a misconception that since cameras can set exposure,  aperture, and focus automatically, it's impossible to take a bad picture, but it's less clear how photography is elevated to art. In software, a customer can see an application that appears to work, and have no idea that the system is riddled with technical debt that will make future maintenance and extension a nightmare.

aperture, and focus automatically, it's impossible to take a bad picture, but it's less clear how photography is elevated to art. In software, a customer can see an application that appears to work, and have no idea that the system is riddled with technical debt that will make future maintenance and extension a nightmare.

I'd love to think that we could educate customers on a massive scale, and in the process, drive out bad development practices because no customer would ever tolerate them, but I'm coming to understand that sometimes, a customer just may not be experienced enough to understand why you're a better value than the "cheap" service.

How are you educating your customers?

Codemash 2.0.1.0

It's CodeMash time again, and once again, I'm taking notes on my Adesso tablet

It's CodeMash time again, and once again, I'm taking notes on my Adesso tablet , and uploading them with Evernote to a CodeMash public folder. You can see all of my scribblings there as I sync and once again, I'll have some posts to follow based on what I'm seeing here. There have already been some really fantastic sessions.

, and uploading them with Evernote to a CodeMash public folder. You can see all of my scribblings there as I sync and once again, I'll have some posts to follow based on what I'm seeing here. There have already been some really fantastic sessions.

Update: If you look at these notes, you'll immediately see two of the most troublesome issues (for me, at least) with the Adesso pad. First, this pad uses a regular 8x11 pad of paper that's clipped onto the Adesso pad. This part is actually pretty great, because I don't need special paper to record notes. In fact, I almost ran out of paper during the conference. With other pads, I might have been done at that point, but with the Adesso, I could (in a pinch), just flip the paper over and write on the back, or grab a flyer or whatever other standard paper might be laying around.

So what's the problem? The pad can slip. If there's any play in the pad on the Adesso tablet, the writing becomes pretty illegible - especially on the bottom of pages. This is pretty apparent in a few spots in these notes.

The other big problem is that it's really easy to record right over the top of a page that's already got notes on it. I've now gotten into the habit of advancing the "electronic" page when I flip the paper page - this bit me regularly for a while after I bought the tablet. Last week, though, I fell victim to another variation on this theme -- the "page forward" and "page back" buttons are located on the left edge of the tablet, and being a lefty, I bumped them accidentally a couple times. Without realizing it, then, I moved the "electronic" page back to one that I'd already recorded, and just kept right on taking notes, resulting in a double-exposed page or two.

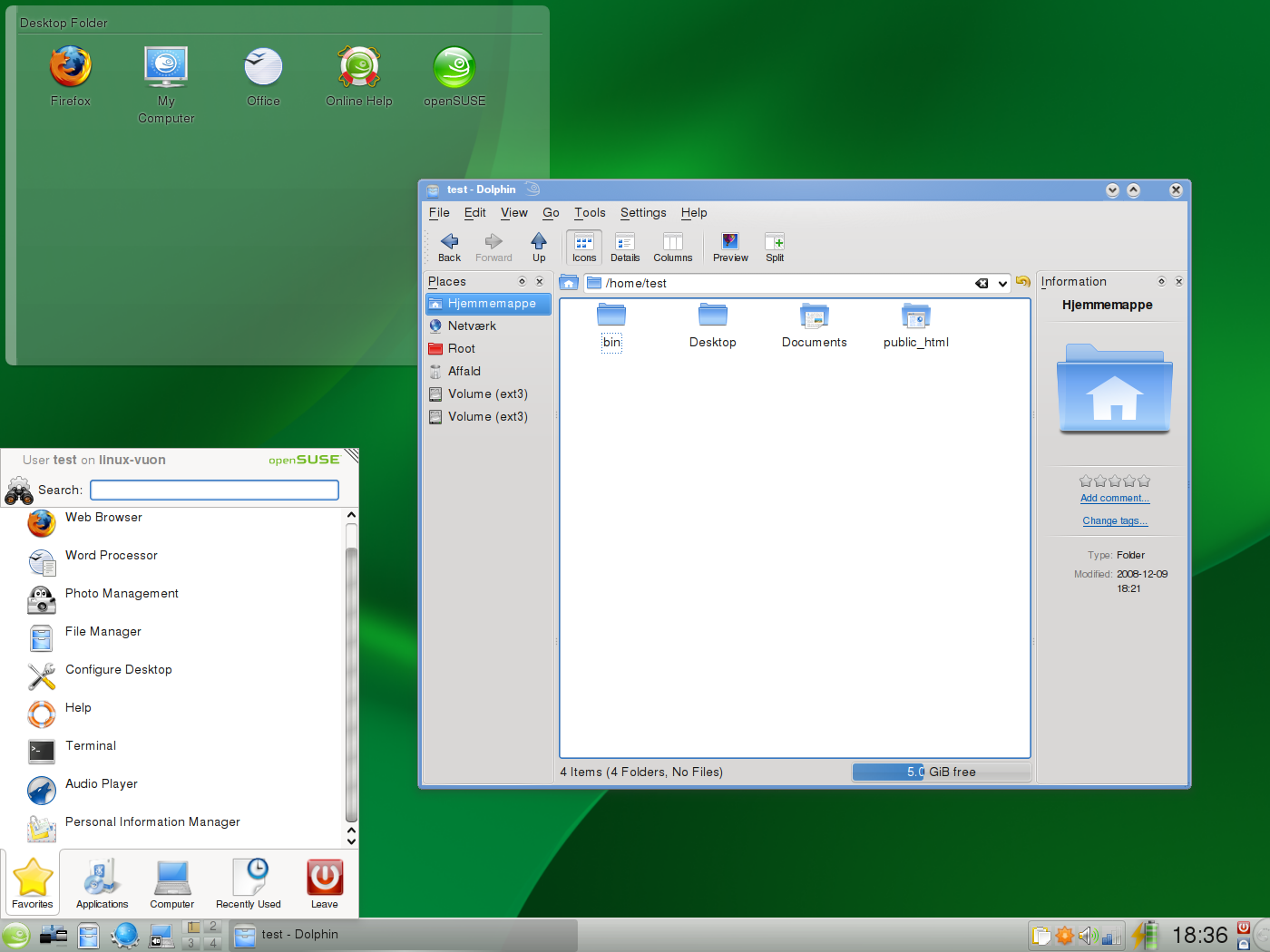

Choosing a Linux Distribution

A while back, a friend asked me some questions about getting started with Linux. He wanted to know specifically whether he should pick up a copy of RedHat at the local retailer -- for something on the order of $80.

I sent him back some notes about choosing a Linux install (distribution, or "distro"), and thought there might be some information here worth repeating. Incidentally, you might find it worth trying a Linux Live CD (see below) even if you don't think you're a Linux person just to see how your hardware performs with another operating system - it can be eye-opening.

[callout title=Gnome or KDE?]When you start looking at distros, you'll immediately notice that most identify themselves as either a Gnome distro or a KDE distro. Gnome and KDE started out as window managers, which meant that they were responsible for displaying, styling and managing the User Interface. Over time, though, both have turned into extensive library installs, much like Microsoft's .Net framework. If you install a lot of applications, you'll eventually end up with most of both frameworks installed, but only one of them (at a time) will actively run your UI. In any event, you should try one of each and see if you give a hoot which one you use. Read more about them here[/callout]

Don't install yet...

Before you install anything at all, you can play with a one or two versions of Linux to see what you like about each of them. The easiest way for most people to do this is with a Live CD. A Live CD (or DVD) is a bootable image of an operating system. Just download the Live CD image (this will most likely be an ISO file), then burn the ISO file to a disc. Leave the disc in your optical drive, reboot your computer, and make sure your computer is set to boot off the optical drive before it boots off your hard drive.

If you followed along to this point, you should see Linux booting off the disc you just created. It'll start up, detect most of your attached devices, acquire a network address via DHCP, and you should end up with a working Linux desktop in just a few minutes without making any permanent changes at all to your machine. When you're done, just eject the CD and reboot back into Windows.

... or don't install at all

The other way to evaluate Linux distros is with a Virtual Machine. Both Virtual PC from Microsoft and VMWare (Player or Server) are free, and both can be incredibly valuable for testing, development, and so on. Between the two, I'd pick VMWare -- it's fast, stable, and widely supported. Plus, if you choose VMWare, you can download pre-built images from their Appliances site. This can be even faster than using a Live CD once you've got VMWare installed.

The family tree

- Image via Wikipedia

There are probably thousands of Linux distributions, or distros. For some sense of scale, see this list or http://distrowatch.com/. Despite these numbers, there are relatively few popular distros, and almost all of them have been formed by "forking" an existing distribution. Thus, any distro you pick will come from a small number of "root" distros. Take a quick look at this diagram to see what I'm talking about.

Although the specific lineage you pick shouldn't matter much, you'll usually see support articles refer to instructions for one or more of these roots, so it's helpful to know if you're running a Suse-based distro, or a Gentoo-based distro, and so on.

For what it's worth, the most popular general-purpose distro right now is probably Ubuntu, so if you're absolutely flummoxed right now about where to start, that would be a fine one to begin with.

But what about RedHat?

If you've made it as far as firing up one or two distros, you'll realize that you're not going to get much in the RedHat box that you don't get for free somewhere else - after all, that's the Linux way. If you still see something on their feature list that you want to pay for, go ahead, though - at least you're an informed buyer now. Of course, if you insist on buying a distro, Suse's enterprise distro is probably worth a look, too.

Related articles by Zemanta

- How to choose a Linux distribution flow chart (ghacks.net)

- 10+ free, fast-booting Linux distros that aren't Chrome OS (downloadsquad.com)

- Ubuntu 10.04 to Include Beginner's Manual [Ubuntu] (lifehacker.com)

Fixed bid isn’t nirvanna

When a business wants a custom software deliverable, there's a basic decision to be made about how this software is sourced, or procured. Like a buy-vs.-lease decision when you go to the car dealership, the business has to decide first if they can and/or will develop the software with internal resources, and if not, they need to solicit bids and pick a vendor to do the work.

- Image by Ikhlasul Amal via Flickr

For many years, the only way to obtain software development expertise from outside your company was to contract that expertise on an hourly basis. In fact, this is still the bedrock upon which most "consulting" firms are based. It's not sexy, but it pays the bills. For customers, however, this can be an unrewarding experience because they still must provide most of the infrastructure of a software development shop, and in many cases, this just isn't feasible.

In order for consulting companies to meet this need, these firms began to sell "solutions." In a broad sense, this is simply an arrangement to bundle all the work for a deliverable and charge per software deliverable, rather than per hour.

Solutions, then, are sold either on a fixed-bid basis, or on a time-and-materials (T&M) basis. I'll forgo a full examination of either of these models here, because most people are familiar with these models. Suffice it to say that "fixed-bid" remains by far the sexier option, because it promises predictable budget-to-expense performance for the business, and predictable forecast-to-revenue performance for the solution provider - both of which make management look great.

In actual practice, however, fixed-bid projects don't always turn out to be quite that tidy. Requirements change, bids are supplemented by change controls, staff turns over, and any number of other minor catastrophes combine to make one or more parties in these transactions wish they'd done things very differently.

Over the last five years, then, any number of IT services companies have swung from 100% staff-aug work to take on a fair number of fixed-bid projects, and many have now started to swing back the other direction because of the pain they've experienced. Fixed-bid is still a sexy sell, but it's now recognized as a tough delivery.

- Image by Fabio Bruna via Flickr

Customers have also had a chance to experience this pain. When you fix the price of an IT deliverable, you're going to experience pain with each and every change you need to make. In many cases, this will even include changes that you don't perceive to be changes at all, merely because requirements weren't spelled out clearly enough in the beginning. Customers who aren't really good at analysis and requirements definition will very likely feel like they've be run through the wringer.

The bottom line for fixed-bid projects: Customers who understand what they want, and can specify this in writing, will do fine in a fixed-bid scenario. These customers are more likely to get the software they want, and their vendors are more likely to deliver this software with a minimum of drama. If a customer doesn't understand what they want, fixed-bid probably isn't the right answer. Instead, concentrate on prototyping or agile development to derive the right answer, but understand that the delivery schedule has to be subject to change as requirements become better understood.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Process Rarely Fixes The Problem (regulargeek.com)

- Software Development Consulting (slideshare.net)

- Survey: Speed (to Market) Kills (devx.com)

Is your Enterprise too big to fail?

We have met the enemy, and it is Complexity.

About a year ago, the media was flooded with debate about financial institutions that were deemed "too big to fail" by industry analysts, financial experts, and government representatives. A failure by one of these institutions, these experts told us, would have catastrophic effects on our economy, and it was therefore incumbent upon us as a nation to keep these firms solvent.

And if you believe this, I've got some great beachfront property in Kansas I'd like to talk to you about.

[callout title=What dependencies?]How, exactly, are all these financial firms connected? Obviously, a full exploration of this is out-of-scope here, but the single biggest problem child in the financial meltdown was the web of financial derivatives, which financial institutions applied as a sort of insurance policy, but which, in the end, turned out to be anything but that. The idea behind these derivatives was to aggregate a bunch of debt obligations together and resell them, and financial firms believed this would act, among other things, as a sort of reinsurance guarding against risk in any of the individual debt obligations. As these things were packaged and repackaged, though, the cumulative effect was to create a virtual ponzi scheme of obligations linking all of these firms together in a frighteningly incestuous fashion.[/callout]

"Too big to fail," you see, resulted directly from "too complicated to understand." The real nightmare scenario for these experts wasn't the failure of a single institution, no matter how big it was -- it was the domino effect where the failure of one institution would cause a chain reaction of failures across all the top financial firms. Here's the killer, though: these experts couldn't tell you which dominoes, exactly, would start a chain reaction, which mean that (1) these experts understood that there were horribly complicated inter-dependencies among these financial firms, and (2) they didn't understand these dependencies well enough to understand what would happen when one failed.

The problems with this scenario go on and on. Very few people have any real grasp on the actual implementation of complex financial instruments within a single organization, let alone the contractual obligations that link firms to firms. This includes the executives running these companies, who, in true empty-suit fashion, blindly accepted whatever horse-hockey they were fed by their underlings because there wasn't a chance in hell that they understood all the details of the operations under their control. This isn't to say that these executives aren't bright guys -- nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the complexity of these operations is so staggering that no one person could ever hope to grasp the whole picture at once.

At this point, you might be wondering what this has to do with software development. Fair enough. The connection is the common problem: complexity.

Software developers are no strangers to complexity. Despite an onslaught of tools, techniques, frameworks, and design patterns which all claim to make Enterprise software development "easy", our applications invariably end up complicated as hell by the time they're installed. I opened a Visual Studio solution the other day that had 43 projects in it. What's worse, this solution clearly followed patterns that have been demonstrated by Microsoft, so there's a clear argument to be made here that this behemoth is crafted according to industry best practices.

- Image via Wikipedia

A developer who's immersed in such a solution can have a ghost of a chance of understanding what's happening among those 43 projects, but just barely, and only if he's really good and really focused on this solution. This is functionally equivalent to a Financial Analyst who understands in great detail how an individual financial derivative is constructed. Like the financial example, though, there's no way that business leaders could ever hope to fathom the complexity of software like this, and they're the ones who are making decisions about it.

This has to end. The status quo is one where our leader don't understand the things they're making decisions about. How is it any wonder that they all behave like pointy-haired bosses?

It turns out that I'm not the only one that believes this. Roger Sessions is a well-known architect and author who's been promoting simplicity since the dawn of the Doppio Macchiato. Recently, he's been supporting his book, Simple Architectures for Complex Enterprises, with some excellent blogging and a white paper, which can be found on the book's companion site.

Honestly, some of Roger's material isn't easy to swallow. Software designers by nature are a pretty self-assured bunch, and usually, that's well-justified, as they're also a pretty bright crowd. We'd all like to believe that the designs we've crafted are perfectly extensible and scalable. Furthermore, we're reluctant to admit that anything is too complicated for us to grok.

It's not easy for business leaders to grasp this stuff, either. Since they're already oblivious to the complexity of these systems, it's a pretty big leap of faith for them to accept that complexity is the problem, and furthermore, that there can actually be a solution.

Adding to this whole mess is the predisposition of nearly all the individual role players to keep right on doing what they've always done. Our understanding of capitalism and efficient markets suggests that groups of people will collectively find efficiency and balance, but when the individuals involved don't really understand how their actions affect outcomes, you start to see some pretty odd collective behavior. Dan Ariely has done some remarkable work exploring this paradox in his book, Predictably Irrational.

All this suggests that it's going to take a pretty phenomenal level of commitment to change the status quo. Let's start by admitting we've got a problem. I believe that Complexity is the #1 problem facing Enterprise software development today, and it needs to be confronted and mastered.

Are you with me?

Related articles by Zemanta

- The Science of Irrational Decisions (science.slashdot.org)

- Are We In Control Of Our Own Decisions? & The Surprising Science Of Motivation (beatschindler.com)

- The Problem With Planning (agile-software-development.com)

- Banks made $5.2B trading derivatives in 2Q (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- The Enterprise 2.0 Crock (soacenter.com)

Agile Leadership: Methodology Ain’t Enough

It's a running joke in software development that as soon as someone demonstrates that he's a good software developer, he's promoted to management, whether he wants it or not.

- Image by Cappellmeister via Flickr

In recent years, of course, many companies have addressed this to some extent, and it's now just as common to see software leaders come from a formal Project Management background, often without having had prior experience in hands-on development. I'd argue that this still isn't ideal, unfortunately, since this simply gives you a business-oriented leader who doesn't understand the technical domain of his or her work.

A recent entry on The Hacker Chick Blog explores this issue, as well (Agile Leadership: Methodology Ain't Enough). Read through this article, and consider a leader with a technical career path vs. a non-technical career path. Is it reasonable to expect someone without a proper technical background to be able to facilitate the sort of interactions Abby describes in her post?

I believe that a really effective direct manager (not a manager-of-managers) really does have to combine technical skills with business skills. One without the other, in my experience, leads to frustration and conflict.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Three Qualities of a Leader (nofluffjuststuff.com)

- It's All About Execution (pongr.com)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?w=525)